OLMS

Composting + Recycling

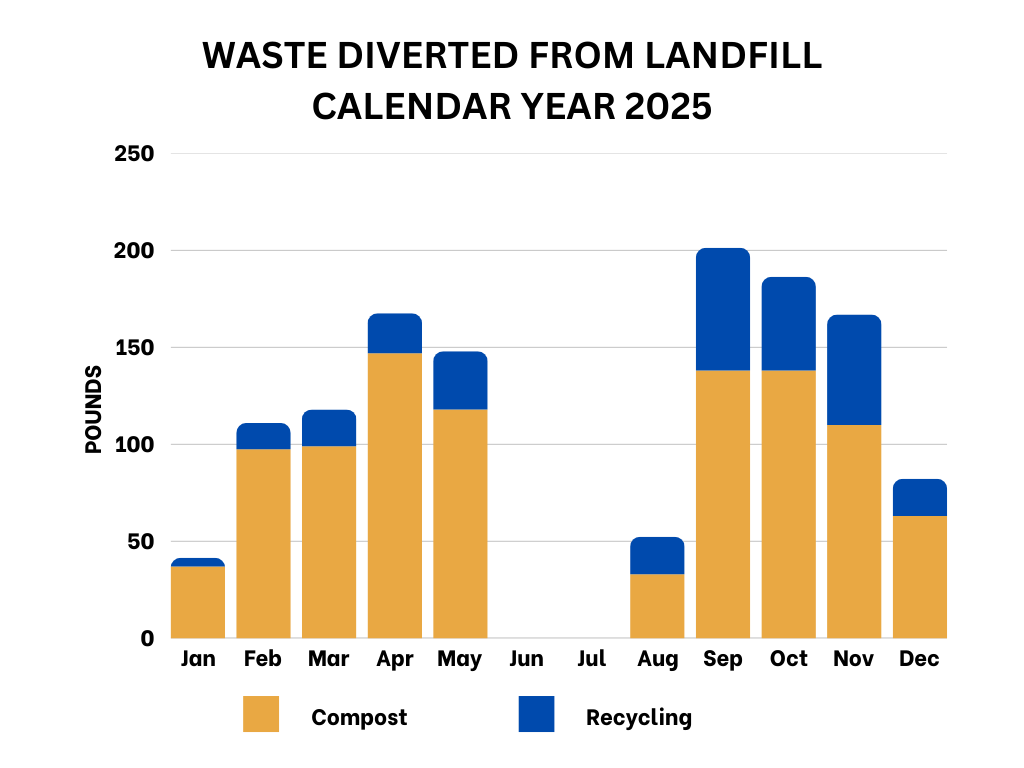

1,275 LBS

OF WASTE DIVERTED

IN 2025!

(Weekly data available here.)

Why compost?

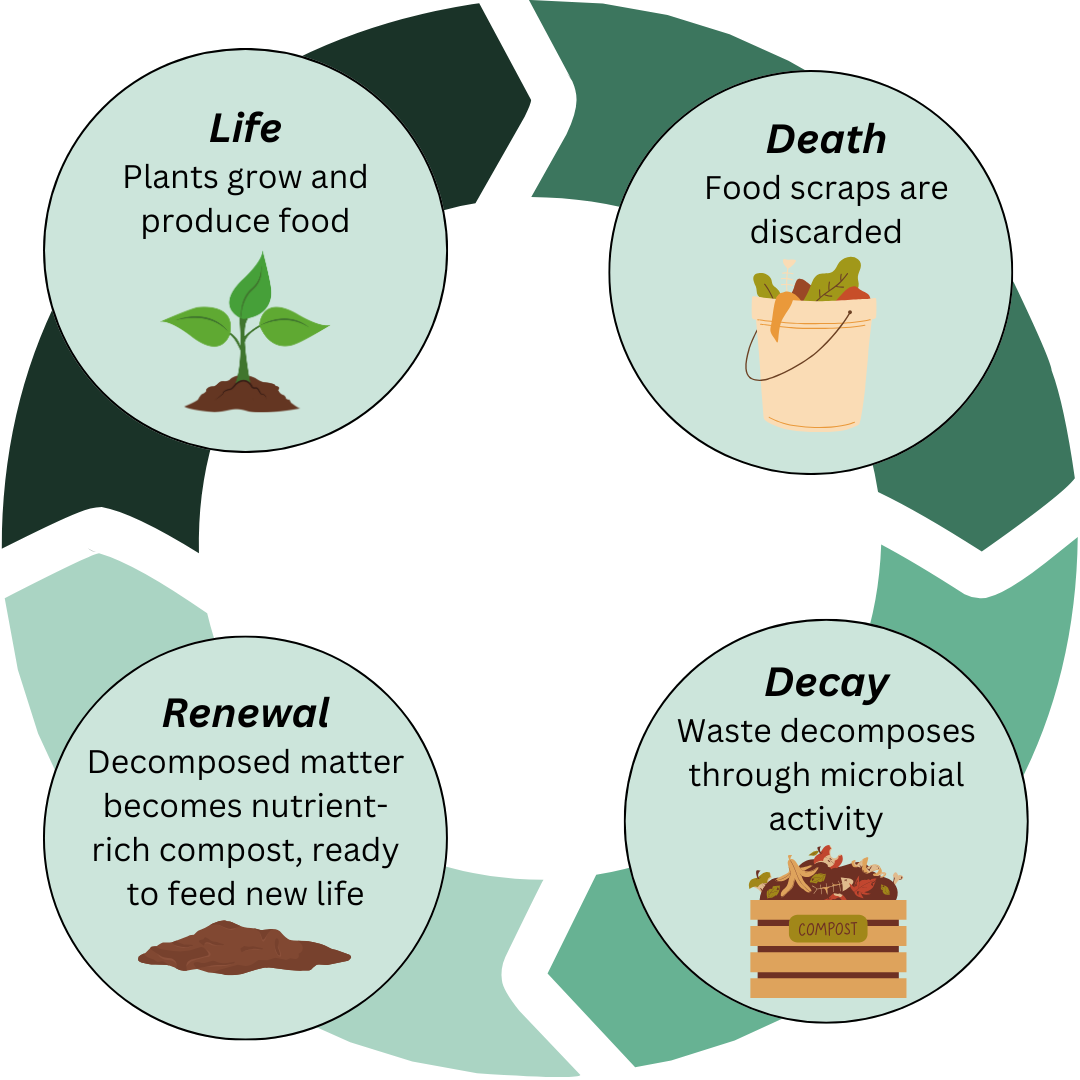

Composting turns food scraps, yard waste, and other organic material into nutrient-rich soil. It is an endlessly regenerative cycle that reduces waste, enriches soil, and nourishes new life (including our food!).

Landfill conditions preclude this regenerative cycle and produce undesirable byproducts.

By diverting our organic waste from landfills, we reap the benefits of composting and we avoid the drawbacks of landfills—it’s a win, win!

How does it work?

There are three waste streams at OLMS:

Compost (yellow bins);

Recycling (blue bins); and

Trash (traditional trash cans—usually black, gray, or white)

A consistent visual presentation of colors and signage helps everyone get in the habit of putting the right waste in the right bin!

Bathrooms have two bins: compost and trash.

Classrooms have three bins: compost, recycling, and trash.

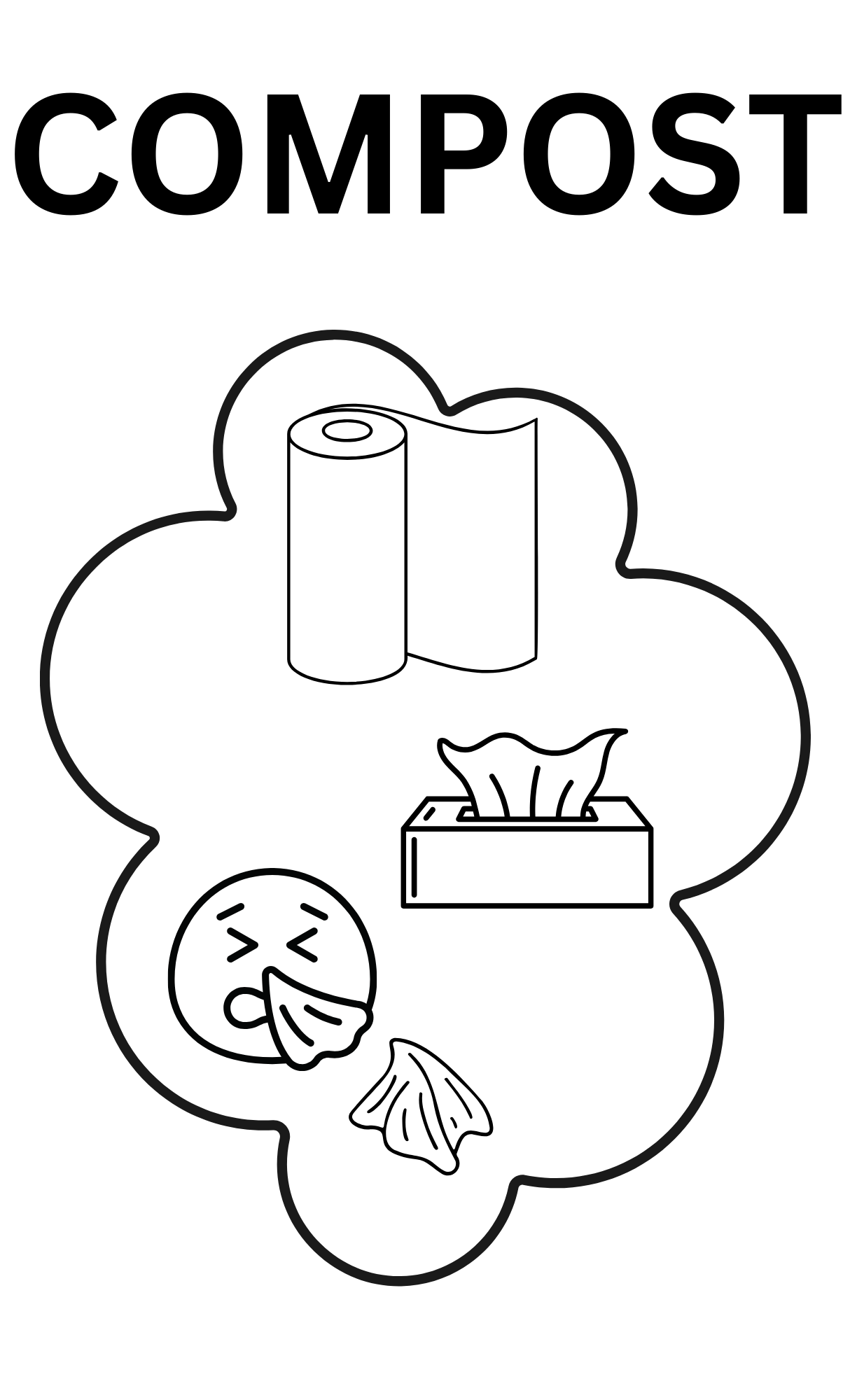

Signage

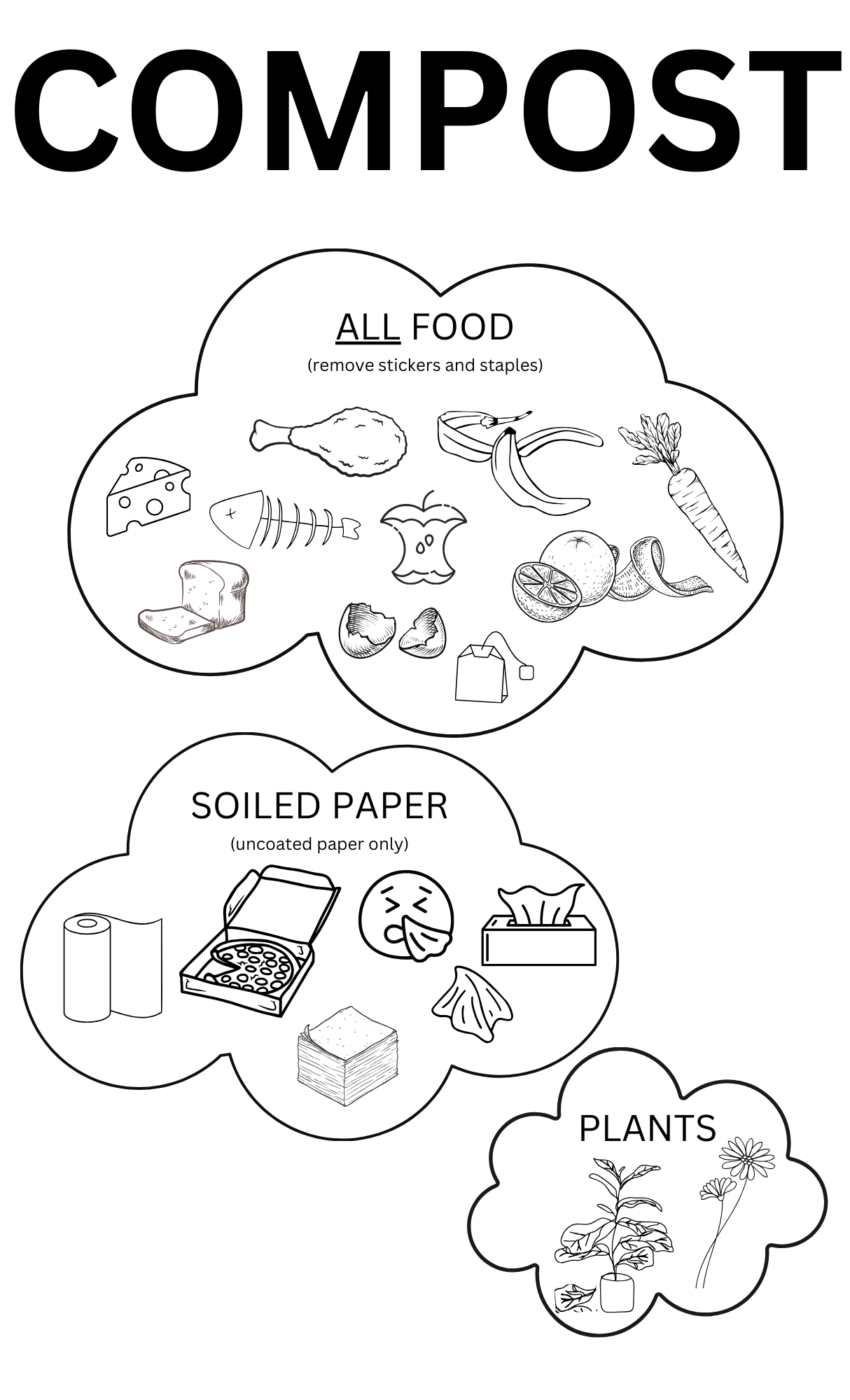

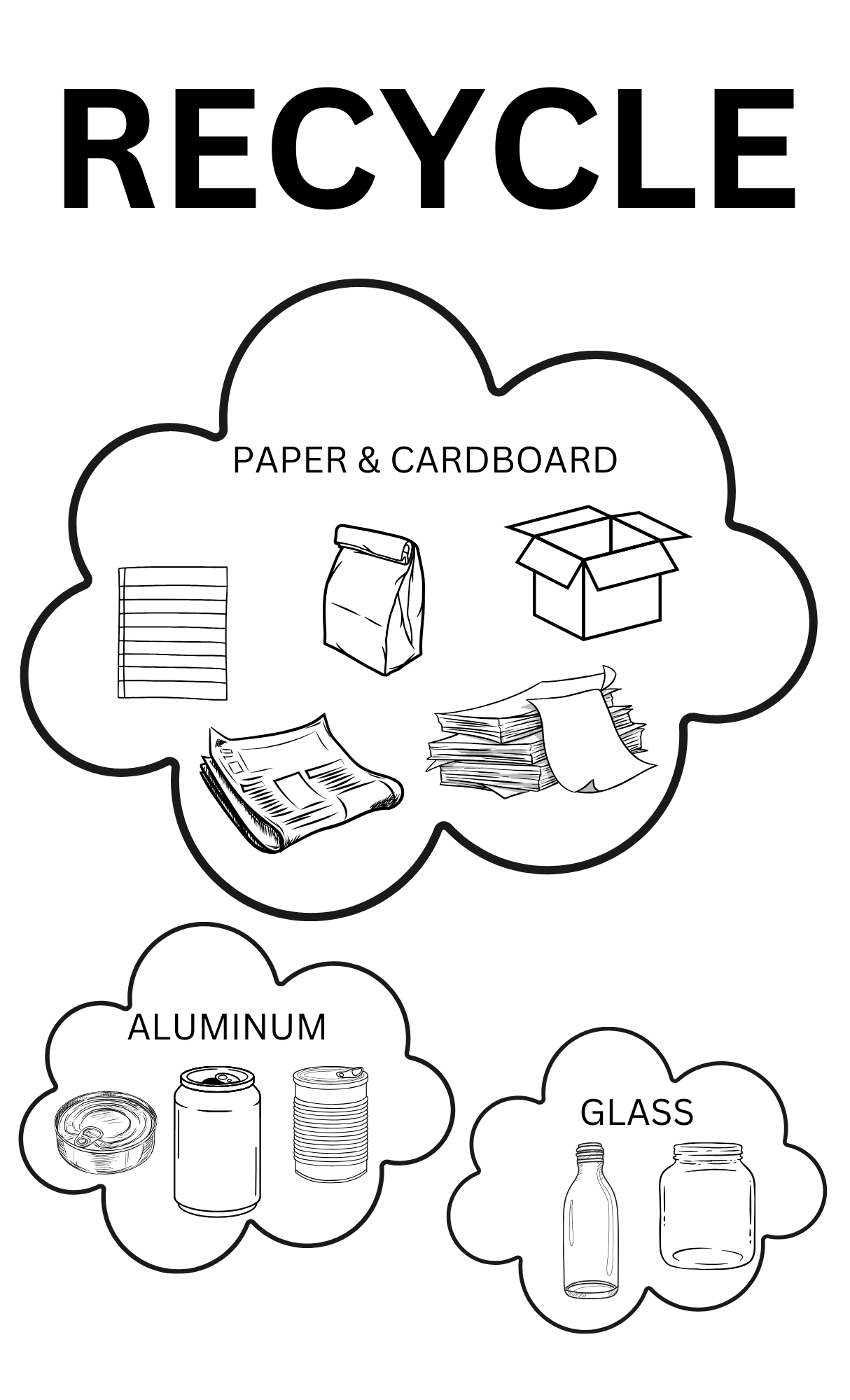

What waste is being diverted?

The most common materials collected in each stream are listed above.

Who collects the waste and where does it go?

At present, compost and recycling bins are emptied daily by volunteers and aggregated for weekly collection. (Contact Jen Schroeder at jen@schroederkc.com if you are interested in volunteering!)

Compost is aggregated in a 64-gallon yellow rolling tote (you may notice it next to the dumpster screen) and collected curbside weekly via a commercial subscription to Compost Collective KC.

Recycling is taken home by volunteers to be recycled in their curbside residential service.

As cross-contamination is reduced (i.e. the right waste consistently goes in the right buckets), older students may begin emptying buckets (as they do the trash).

FAQs

-

Yes! In addition to starting a compost pile in your backyard, there are several great “hands-off” options at various price points.

FREE! - Drop your compostable materials for FREE at Urbavore Urban Farm’s compost trailer. Details here: https://www.compostcollectivekc.com/drop-off

FREE for KCMO residents - Drop your compostable materials in one of KC Can Compost’s “smart cans” (there are 3 around the City). Details here: https://kccancompost.com/kccansmartcan

$8 per bucket - Swap your full bin for a fresh one at over 20 spots across the metro. Details here: https://www.compostcollectivekc.com/binswap

$13 per month - Empty your full bin as often as you’d like at over a dozen spots across the metro. Details here: https://kccancompost.com/locations

$20-30 per month - Curbside pickup—doesn’t get any easier than this! Simply place your full bucket on the curb (either weekly or bi-weekly) on your regular trash day—that’s it! Details here: https://www.compostcollectivekc.com/curbside-composting

**If you would be interested in dropping your family’s food scraps and other compostable materials at OLMS for $5-10 per month, please let Jen Schroeder know (jen@schroederkc.com) so that we can gauge interest in a community bin.

-

Yes! Volunteers collect compost and recycling buckets daily. This takes 15-30 minutes and is generally done at the end of the day, around 2:45 or 3:00 p.m.

If you would like to volunteer, email Jen Schroeder at jen@schroederkc.com.

-

Ideally, we compost or recycle as much as possible. But if we're not sure about something, it's better to throw it away than to risk contaminating the composting or recycling streams.

Contaminants in composting and recycling streams can cause real problems for those processes.

For compost, the contaminants go straight into the soil and can cause environmental harm.

For recycling, contaminants can damage machinery and/or taint an entire batch of materials, causing the batch to be trashed rather than recycled.

-

Plastic, by far.

If we can get all plastic wrappers, pouches, sandwich bags, half-eaten yogurt cups, and similar items into the trash, we will eliminate nearly all of our contaminants!

At a distant second, paper towels and tissues are sometimes placed in recycling. These items are not recyclable, but they are compostable—they can always go in the compost!

-

Plastic waste is a tremendous problem, and recycling is—at best—a partial, significantly flawed solution (more details in the next FAQ). Thus, the primary goal is to reduce plastic consumption as much as possible.

With that said, there are two types of plastic waste: (1) “single-use plastic,” which cannot be recycled and must go in the trash, and (2) plastic that is eligible for curbside recycling.

Nearly all plastic waste at OLMS is single-use plastic—i.e. trash that cannot be recycled. This includes plastic wrappers, pouches, sandwich bags, and other similar items. None of this can be recycled.

Single-use plastics are the single biggest source of cross-contamination in the recycling and compost buckets at school. This is especially problematic for composting, because the plastic ends up in finished compost. Local farmers literally pick plastic produce stickers out of their fields.

Thus, at school, we emphasize that single-use plastics must go in the trash.

Occasionally, a student or teacher might have a #1 (PET) water bottle or a #2 (HDPE) container. These are two of the more recyclable forms of plastic and may go in the recycling bins.

-

Plastic is more akin to a harmful pollutant than a “full circle” product.

Plastic does not decompose into dirt, as organic matter does. Instead, plastic breaks down into tiny particles called “microplastics,” which persist in our environment and contaminate our food and water.

Recycling is not an adequate solution to the problem of plastic waste for many reasons, several of which are mentioned below.

Most plastics—even those that are technically eligible for recycling—are not / cannot be recycled into useful end products. This is because plastic poses unique challenges when it comes to recycling processes. Plus, virgin plastic is often less expensive and higher quality than recycled plastic, so there is not a strong market for recycled plastic.

Not all plastic is equally suitable for recycling. Even within the recycling codes printed on the bottom of plastic containers, different types of containers are treated differently. For example, #1 plastics (PET) are recyclable in bottle form, but clamshell forms can be more difficult to process.

A significant quantity of U.S. plastic waste is shipped abroad, where it is sometimes disposed of irresponsibly (e.g., burned, dumped in the ocean), rather than recycled. And even when plastic is recycled, whether domestically or abroad, the recycling process leeches harmful contaminants (e.g., chemicals, microplastics) into the environment. Chemicals found in plastics are linked to many serious health risks, so this contamination is a major concern.

In sum, although recycling eligible plastic may be a worthwhile endeavor, it is important to stay focused on the larger goal—reduce our consumption of plastic products and plastic packaging as much as possible.

-

Certain paper products are only compostable.

For example, absorbent paper products—like paper towels, napkins, and facial tissue—are only compostable, not recyclable. These always go in the compost.

Similarly, paper products with food residue (e.g., a greasy pizza box) are only compostable, not recyclable. These always go in the compost.

Beyond that, many paper products—like office paper, cardboard, and chipboard—can be either recycled or composted. So it's a matter of first choice/second choice.

Recycling is generally the first choice, because it allows paper to be reused. (Although the recycling process is not free from flaws, so reducing consumption is always the very best route.)

Compost is the second choice, because it is the "end of the line" (i.e. the paper returns to dirt). But note that paper can be a valuable addition to the composting process, and composting keeps paper out of the landfill (where conditions prevent paper from turning into healthy soil), so it's still a "good" choice.

Recyclable paper includes most "office" papers—lined paper, copy paper, construction paper, newspapers, magazines, junk mail, etc.—as well as cardboard, paperboard, and chipboard.

The recycling process is fairly resilient to things like tape and staples (as opposed to composting, which cannot accept plastic or metal), so as long as the tape and staples are not excessive, the paper and cardboard can go straight into the recycling. (An example of "excessive" tape or staples would be a piece of paper that is completely covered in tape as part of an art project.)

Office paper is also compostable, so if recycling is not available, or if the paper cannot be recycled for some reason (e.g., it's shredded, or it's covered in food residue), you can compost it. Just be sure to remove staples, tape, or other non-paper materials first.

Plastic-coated paper is neither recyclable nor compostable. It must go in the trash.

In sum, the guiding principle might be stated as follows: When possible, recycle paper; when recycling is not possible, and when the paper is compostable, compost it.